Disneyland Paris. Today, it stands as the most popular theme park in Europe, with millions of visitors per year. However, things weren’t always so amusant in France.

From its opening day in 1992, the park once known as Euro Disneyland was plagued by cultural clashes, financial woes, marketing snafus, and even a terrorist attack — a (horrible) perfect storm that almost led to this park’s demise and ultimately changed the course of Disney history forever.

Today, we look back at the Disney Parks history Disney would rather you forget.

Crossing the Pond

Walt Disney World was, and remains, one of Disney’s biggest successes; a self-contained vacation destination that dominates the local landscape and economy, filled with room for expansion. From a corporate perspective, Disney World is the platonic ideal of a theme park. There was just one problem: while Disney World was huge, the real world was a lot bigger. There was an enormous market waiting overseas. Disney is big overseas. Big in ways that American audiences might not realize.

Topolino (Mickey Mouse) is one of the most popular comic magazines in Italy, with similar digests (Kalle Anka in Sweden, and Aku Ankka in Finland, both named for Donald Duck) achieving similar popularity around Europe. The so-called Sensational Six (Mickey and friends) are arguably more popular in Europe than they are in the United States, with Donald being the most popular in most places! There’s a reason why one of the most famous advertisements for Disneyland Paris focuses on Donald Duck comics.

Building a theme park in Europe was a natural choice, especially since Tokyo Disneyland was such a wild success. The only issue was a choice of location. While Italy was a natural choice due to the popularity of the Topolino comics, it lacked a stretch of land big enough to fit Disney’s needs; the British Isles had a similar issue. Other countries had inappropriate weather, harsh terrain, or simply weren’t big enough tourist hubs. That left Disney with two choices… the relatively temperate Spain, or the wide expanses of the French countryside. Disney went with the latter, as France’s proximity to the British Isles and status as a major tourist destination would make it more accessible to the majority of European tourists.

In the years following the park’s opening, it would become apparent that this may not have been the wisest choice.

The Infamous Opening Day

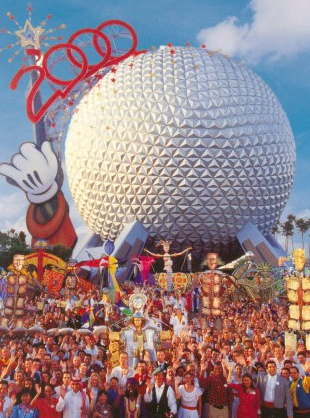

On April 12th, 1992, Euro Disneyland opened to… mediocre fanfare. Yes, there was the customary fireworks show and ribbon cutting ceremony. Parades, shows, all the typical spectacle. However, for a park built to accommodate 60,000 guests, only about 25,000 showed up.

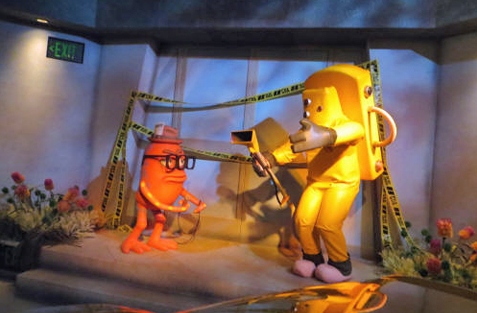

It’s not that Euro Disneyland was a bad park. On the contrary, it was Disney’s most elaborately designed, well-thought-out theme park yet! Only Shanghai Disneyland and Tokyo DisneySea can hold a candle to the raw level of detail and design that went into this park; there’s no other park like it. Yet, within a few years of opening, it was already facing bankruptcy. Why?

Cultural Chernobyl

Disney knew that building a fairy tale theme park in Europe would be a tall order, as many elements Americans find exotic (like Castles) are common tourist attractions in France. To their credit, they did an excellent job on the design angle. However, they failed to account for one big thing.

You see, Disney went out of its way to try to accommodate European culture. It’s even in the name Euro Disneyland. The issue? There’s no such thing as European culture. There’s Italian culture, Spanish culture, British culture, Irish culture… hundreds of different cultures that aren’t even consistent within the same country sometimes! Disney was a predominantly American company trying to tailor a theme park for a collection of cultures they didn’t fully understand… and that’s before we even get into French culture. Because the clash between Disney and their host country is infamous.

You see, while Disney is popular in France, it lacks the same cultural resonance that it does in many other places. That’s because France is fiercely protective of their own cultural product and skeptical of cultural imports from other nations. In fact, Euro Disneyland opened during the height of the cultural exception debate. Let’s break for a quick Social Studies lesson so you’ll see what I mean.

Back in 1947, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was passed in Geneva, Switzerland. The goal was to reduce barriers to international trade, like taxes on imported goods or quotas that limited the number of goods that could be imported. This agreement originally applied to everything, but in the early 90s France began to question its applicability to cultural exports. France was concerned about cultural imperialism: the promotion and imposition of a more powerful culture over a less powerful one. Basically, France was worried that American cultural exports would slowly choke out their local culture.

So, in a revision to the GATT, they proposed a measure that would exempt cultural exports like movies, television, and music from the agreement, allowing countries to give preference to locally produced artwork. Needless to say, this was hotly debated, with France as the largest proponent of the measure. Foreign interests… particularly American interests, like Disney… were viewed as existential threats to French culture. So, when Disney began building a theme park in France, critics weren’t happy.

French journalist Jean Cau famously described the park as “a cultural Chernobyl”, referencing the infamous nuclear disaster, “one that will contaminate millions of children (and their parents), castrate their imaginations, paw their dreams with greenish hands. Green, like the color of the dollar.”

Think pieces like this raged around the park during its construction and earlier years. Shortly before the park opened, a failed terror attack nearly cut power to the entire park. Protestors assaulted then-CEO Michael Eisner with ketchup upon his arrival in the country. Locals to Marne-la-Vallee, already upset by Disney’s purchase of huge tracts of land near their homes, viewed the park with cold skepticism at best and outright hostility at worst.

Of course, Disney wasn’t concerned. Relying on the winning strategy that had brought millions of guests to their domestic theme parks, they produced nostalgic advertisements aimed at drawing children (and children at heart) to the new park. This was another miscalculation. While the ads succeeded in getting children around Europe excited for the new park, they ultimately are not the ones responsible for booking vacations.

Moreover, the targeting of children in advertisements only added fuel to the fire of debate, making already skeptical parents even more reluctant to visit the new attraction. Not that Disney was aware of this, of course. Until opening day, the park projected to overflowing with guests; so much so that local news outlets issued warnings for people to avoid the sure-to-be clogged roads. Locals, already skeptical of the park to begin with, complied… which meant much smaller crowds than Disney could have anticipated, as guests avoided the supposedly overcrowded park en-masse.

The cultural clash also carried over to the park’s interior, as Disney was operating on flawed information. For instance, they downsized breakfast service under the assumption that Europeans “didn’t take breakfast”, leading to massive rushes as guests skipped croissants and coffee for bacon and eggs. Limited access to food during the traditional lunch hour also a shock. As Disney accustomed to the flexible dining schedules of American patrons. The traditional refusal to serve alcohol at the park also a huge shock. As many guests were accustomed to having ready access to wine or beer with their meals.

Guests also didn’t necessarily adhere to the tourism model Disney had found such success with at Walt Disney World. Huge, multi-day attractions were a rarity in France, with many locals viewing theme parks as a day trip. While Disney surrounded the park with beautiful hotels, few guests were willing to take the week-long vacations Disney expected them to. Moreover, the park’s proximity to Paris meant many guests chose to stay in the capital, with the park serving as a mere diversion, rather than a main attraction.

Even the park’s cast wasn’t immune to these cultural snafus. While Disney tried to appeal to French labor unions by hiring full-time staff (as opposed to the part-time, seasonal staff used in domestic parks), traditional corporate measures like the “Disney Look” were viewed as an attack on employee freedom, leading to mass resignations.

The final nail in the coffin? An economic recession hit shortly after the park’s opening, leading many European tourists to skip out on the expensive Disney vacation instead.

The Aftermath

By 1994, Euro Disneyland had over three billion dollars of debt and was on the verge of closure. In a last ditch effort to save the park, Disney changed its name to Disneyland Paris. Made deals with investors and banks to defer payment. Opened their own version of Space Mountain to attract guests back to the park. This radical rebranding, combined with the passing of the recession and the collective realization that comparing. The park to a nuclear disaster kind of an exaggeration, allowed the park to flourish. Today, the park enjoys resounding success as the most visited park in Europe, and one of the most beautiful iterations of Disneyland in the world… but not without cost.

You see, for Disneyland Paris to live, other dreams would have to die. One of the biggest WestCOT, a proposed expansion of Disneyland Resort in California that would have the most ambitious park Disney ever built. Alas, the massive losses in France meant that Disney would have to scale back their plans for Anaheim into something smaller. And that’s how the world got: